Time isn’t the main thing. It’s the only thing.

— Miles Davis

Arguably the toughest part of this whole “making time for yourself” practice is learning how to setup—and enforce—the boundaries necessary to hold that time as your own. This is true both at work as well as home.

In too many workplaces, whether self-employed or part of a team, it’s easy to block time for something and then have another thing come up: the boss drops a calendar invite, a prospective client asks to schedule a call, some “fire” needs to be put out, and so on.

And on the home front, social invitations pop up, family obligations are frequent, and seemingly-important obstacles appear out of thin air.

The reality is this: your time is important.

If you don’t respect that reality, nobody else will.

Perhaps that’s your first step: admitting to yourself that your time is your asset, it is valuable and important to you, and it is worthy of your protection as well as your intentional use.

By that logic, if your time is important to you, then it’s also important to those who value you. Your colleagues, bosses, peers, friends, family, and all those people with whom you regularly interact. If they want you to be happy, healthy, productive, and fulfilled, they need to understand that your time is important to you, and that you respect and value how you spend it.

Effectively protecting your time starts with setting boundaries and precedent, and continues in the form of ongoing efforts to hold steady along those boundaries.

The battle for your time and attention

Setting boundaries is less than half the battle. The real work lies in enforcing those boundaries.

It’s easy to block time on your calendar and tell people you’re unavailable, but when that “fire” comes up and you feel pulled away from what you really wanted to be doing, you are the only one who can make the decision to protect and hold your time for yourself—or surrender your control to the forces around you.

In effort to push back on those forces, a strong starting point is to understand the difference between what’s priority and what’s an emergency. By cultivating a sense of the difference between what’s important and what’s urgent, you will then be able to know when to flex those boundaries and when to hold firm.

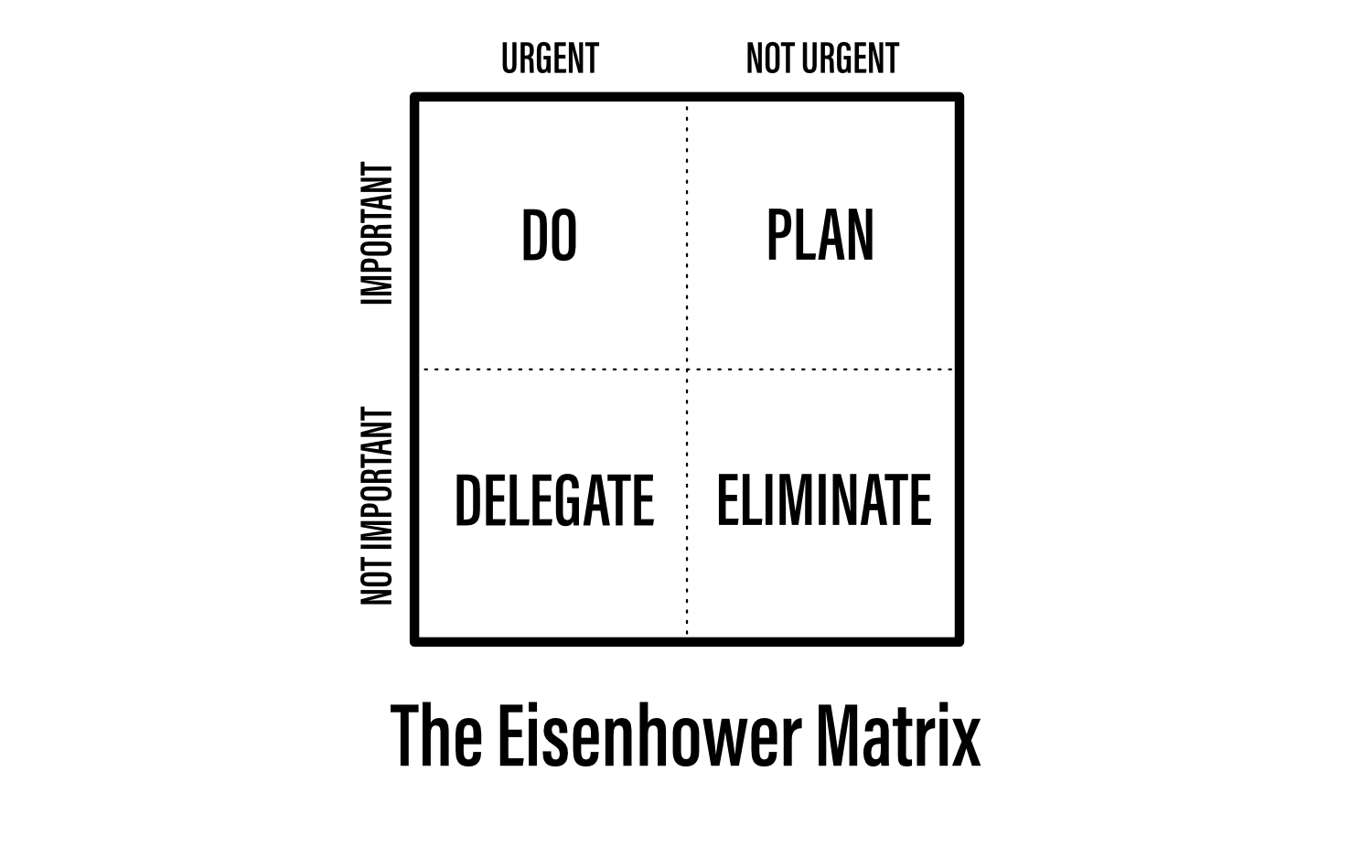

To explore this concept, let’s turn to the age-old 2-by-2 created by former President Dwight D. Eisenhower:

It’s self-explanatory, really, so we won’t spend much time talking about it. In short, there are four quadrants where the urgent and important can intersect. While this matrix proposes four actions—do, plan, delegate, eliminate—the point we want to get across is that there are cardinal differences between important and urgent, and knowing them can help you protect the time you reclaim for yourself in this exercise.

When someone tries to insert themselves into your time, even if something is important, it can wait. If it’s urgent, that might mean you bend a little and surrender some of your time because of that urgency. But unless something is urgent, it can wait, and you have every right to move the “doing” of that task to some point in the future.

You don’t owe people an explanation

Originally this section was titled “How to explain to people that your time is important to you so they give you space and leave you alone to do what you want to do.”

OK, kidding. Not entirely—that’s a bit embellished. But it did start out as “How to say no to people.”

As it was being written, however, we revisited one of our key tenets: you don’t owe people an explanation.

We say this because when you have a doctor’s appointment, you don’t have to explain yourself. When you’re not feeling well, or you have a family emergency, or something comes up that clearly takes priority over everything else, you don’t go around explaining to people why you missed a meeting or why you can’t make it to their party. You simply do what you need to do, and that’s that.

In this spirit we believe it’s important to recognize that you don’t owe people an explanation for how you spend your time. Whether at home or at work, people will want to know what you’re doing. It’s human nature to be curious and inquisitive. However, it’s also in your nature to have privacy and independence, and not have to justify how you spend your time.

So when people ask you if you can rearrange that calendar block, or invite you to a thing during time you’ve reserved for yourself, you have every right to tell them “I’m sorry but that time doesn’t work for me” and then leave it at that. Often times these are situations where less is truly more. The less you say about how you’re spending your time, the more people will respect your need for it.